Two days ago — and three days ago — I visited the German Boma in Arusha.

Some places ask for more than one visit. Not because you missed details, but because the first encounter stays with you and quietly pulls you back.

The Boma is silent.

Not abandoned silence — but disciplined silence. A silence that feels trained.

As you walk through the compound, your footsteps sound unfamiliar, almost wrong. The ground feels accustomed to boots, to routine movement, to order repeated every day at the same pace. This was not just a building. It was a military system made of stone.

A Colonial Outpost of Order

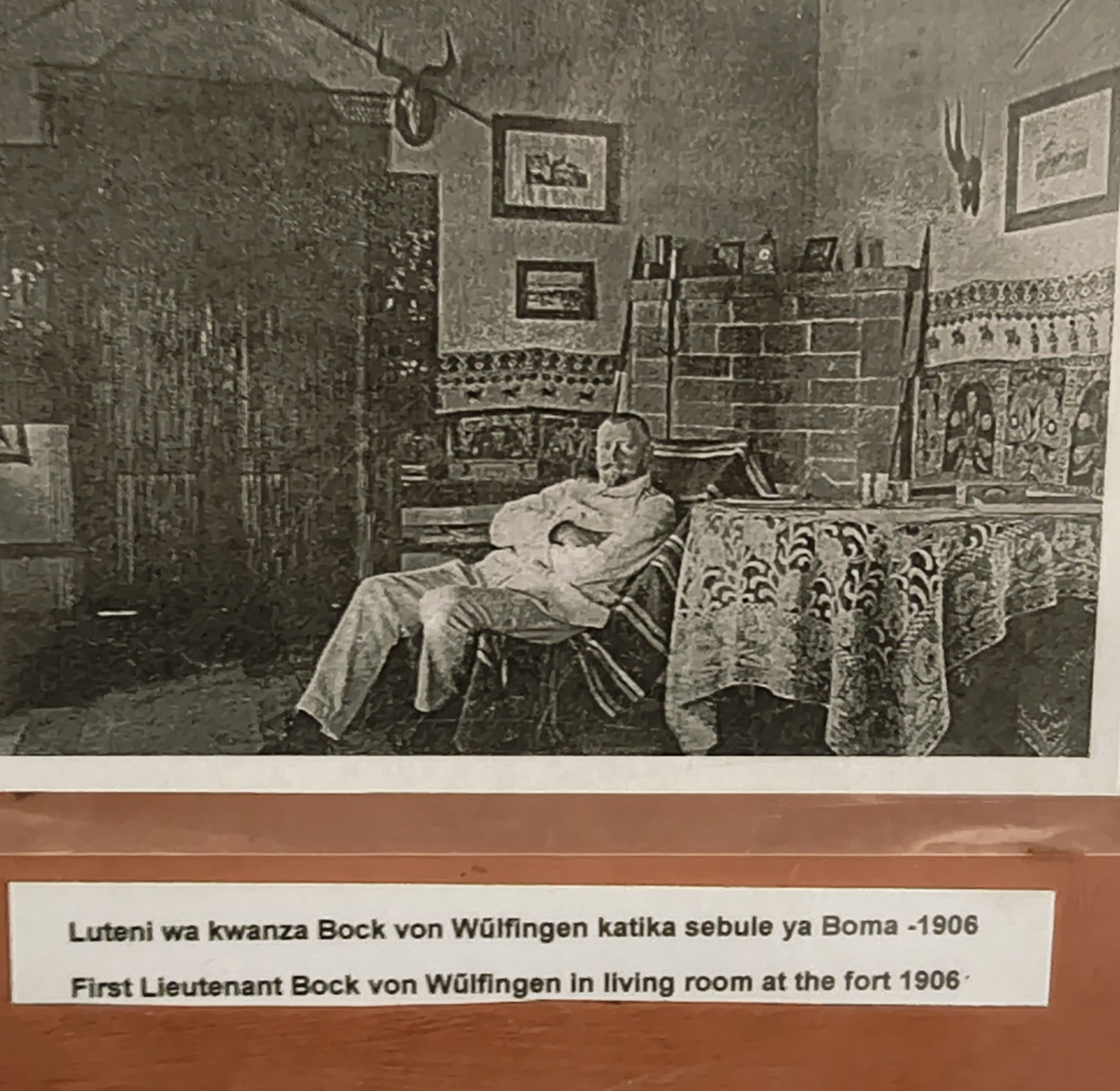

The German Boma was built around 1899–1900, during the expansion of German East Africa.[1] It served as a fortified administrative and military center — a place where authority was enforced, organized, and made visible.

German colonial rule relied heavily on routine discipline: scheduled inspections, forced labor, punishment carried out publicly and predictably.[2] Power did not need chaos. It needed structure.

Standing inside the compound, you can still feel that mindset.

The walls do not feel defensive — they feel instructional.

The Ring Above the Gate

Above the main gate, there is a metal ring.

I was told what it was used for.

Executions took place there. A rope attached to the ring. People were hanged and left there — not briefly, but long enough to be seen.[3] Long enough for fear to travel. Colonial punishment was not only about death; it was about demonstration.

Seeing that ring, the architecture changes.

The gate is no longer an entrance. It becomes a warning.

Waste, Fire, Erasure

Inside the complex, I was shown another area.

A place where trash was thrown.

And where bodies were taken.

Colonial bomas commonly combined refuse disposal with the burning of bodies, especially after executions or deaths in custody.[4] Those who were no longer useful — or no longer alive — were reduced to something meant to disappear.

It is unsettling how ordinary the space looks today.

No monument. No sign. Just ground holding what it once consumed.

Colonial systems often erased twice:

first the person, then the memory.

The Prison Below

Then there is the former prison.

It goes down.

Into the earth.

A hole rather than a room.

German colonial detention facilities were frequently designed below ground, minimizing light and airflow.[5] This was not just confinement — it was removal. From light. From sound. From time.

Standing above it, you understand that imprisonment here was meant to shrink a person, to make them disappear while still alive.

The silence there is heavy.

It presses inward.

What Remains

What stayed with me most was not shock, but how intact the atmosphere still is.

The Boma is preserved. Clean. Orderly. Even beautiful in a restrained way. And that is exactly what makes it disturbing. The symmetry, the calm, the maintenance all echo the logic of colonial rule: order over humanity, structure over life.

You can almost smell the past.

Not decay — but routine.

The daily run of an empire operating far from home, convinced of its permanence.

Some historical sites explain everything with signs and plaques.

This one does something else.

It lets you stand.

It lets you listen.

And if you stay quiet long enough, the silence tells the story.

Footnotes & Sources

[1]: Natural History National Museum (Old German Boma), Arusha — museum records and Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources & Tourism; see also: Wikipedia, “Arusha” and “German East Africa”.

[2]: John Iliffe, A Modern History of Tanganyika, Cambridge University Press — on German colonial administration, forced labor, and discipline.

[3]: Jürgen Zimmerer, Colonial Genocide and German Rule in East Africa, on public punishment and execution as tools of colonial control.

[4]: Jan-Georg Deutsch, Emancipation without Abolition in German East Africa, on colonial practices surrounding death, punishment, and erasure.

[5]: Thaddeus Sunseri, Wielding the Ax: State Forestry and Social Conflict in Tanzania, referencing colonial detention and punishment structures.