UnHerd

Why do so many students have ADHD?

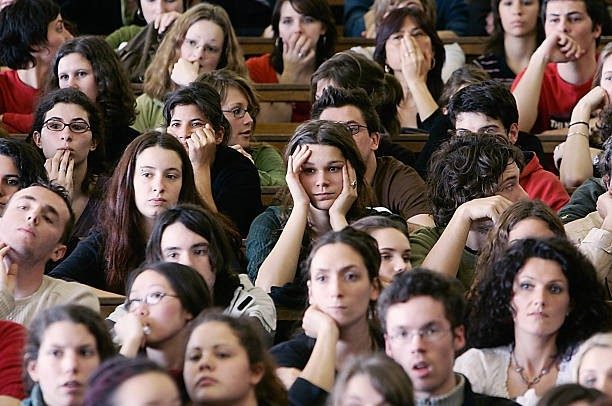

I’ve been teaching in British universities for about 15 years and over that time, I’ve watched a few trends unfold. Like when they started needing safe spaces and denying basic facts about human biology. (That’s basically over now, by the way.) Or wearing hideous footwear, and dressing in androgynous black-and-white clothing. All of it the wrong size. (It’s not me that’s mistaken, it’s the kids.) But probably most noteworthy is the dramatic increase in students entitled to special accommodations because of disability. Every year, more essays come in after the deadlines, because more students get extensions lasting weeks, even months. On Mondays I receive automated emails reminding me to be very careful when asking certain students questions in seminars, or expecting them to contribute in any way (apparently, they might not be able to handle it if I do). Despite the fact that I teach political philosophy — a subject impossible to execute without precise handling of language — the university bureaucracy says that the quality of written language needs to be disregarded when assessing some candidates’ coursework. All of this, and more, is due to accommodations made under the rubric of disability.

This explosion has not been driven by campuses suddenly becoming wheelchair accessible. (I happen to be a wheelchair user myself, and so I assure you that I take disability very seriously.) Instead, students are being diagnosed with impairment disorders relating to their ability to learn. And of these, four constitute the bulk: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, and non-profound autism spectrum disorder (ASD). So what is going on? The truth is, it’s complicated. And as a result, two of the most common answers just won’t do. The first answer (which The Atlantic reporting leans towards) is that it’s basically all a scam. Here’s the thing: students with registered disabilities are eligible for deadline extensions, extra time during exams, and a whole raft of entitlements regarding seminar attendance and participation. Having realised that students with impairment diagnoses get such special consideration, sharp-elbowed middle-class parents reckon it is a sure-fire way to win their offspring competitive advantage. Shopping around for helpful diagnoses from pliant physicians, the aspirational classes respond to prevailing incentives. Cue the surge in presentation of the disorders.

To be fair, The Atlantic’s assessment isn’t completely wrong. Sometimes the lengths to which privileged parents will go for their kids are truly astonishing, especially in the United States.